The Web’s Most Tolerated Feature

Posted by Mike Pennisi

Were you around for June 19, 2000? It was a great day! There we were, the human race, collectively: just kicking off the summer, waiting in line for Gone in 60 Seconds, digging in to our McSalad Shakers, yet greedily wondering who could take us still higher. Even Microsoft Corporation (MSFT) was living its best life, releasing version 5.5 of the Internet Explorer (IE) web browser.

But oh, we were all so naive! Lurking just beneath the gaiety and hair gel was

a tiny non-standard feature that would grow to grotesque proportions. In the

process, it would inspire confusion, bug reports, workarounds, and blog posts.

zoom was its name, and we are only just now coming to terms with its

turpitude.

Ambitious beginnings

The idea behind zoom was fairly simple: allow developers to visually expand

or shrink any given element. Set zoom: 2, and the element would double in

size. zoom: 0.1, and it’d shrink by a factor of ten. And et cetera!

Naturally, it would push/pull the surrounding elements to accommodate its new

dimensions.

The only trouble was, no one took the time to write a formal specification for

this behavior. zoom was just one of many features that browsers used to

differentiate themselves on the market. The fragmented nature of the early web

platform is well-documented, but suffice it to say: it wasn’t good for

developers, and it wasn’t good for the web’s users.

That’s why, over the early years of its existence, zoom had largely been

adopted only as digital window dressing–some sites looked nicer with it, but

they would still function without it.

A fresh start

The largely-superfluous nature of zoom was important for Mozilla, which made

standards-compliance a priority from day one. As it prepared Firefox for a

stable release in 2004, it was able to ignore zoom and instead focus on

technology that had clear acceptance criteria.

It wasn’t long before the web standards bodies designed CSS

transform. Not

only did this new property grant developers zoom-like behavior; it allowed

for even more control over the shape of elements, and it could be done more

efficiently on low-powered devices. True, it wasn’t exactly the same

(transforming an element would not impact the position of its neighbors), but

to the extent that Mozilla had previously felt compelled to reverse-engineer

IE’s zoom, supporting transform was a sort of pressure-release valve.

Apple took a more expansive (albeit costly) approach: it implemented everything. Safari 3.5 introduced support for transform, and the next release added zoom (including, perhaps unavoidably, its own quirks) on top of that.

Thus, zoom entered a truly liminal state on the web platform: ignored by the

committees, implemented inconsistently by some engines, rejected by other

engines, and regarded with suspicion by web developers.

Misleading popularity

A few years ago, Mozilla and Bocoup teamed up to prioritize the features that

Firefox alone didn’t

support.

zoom was on the list, but that was more for completeness than anything else.

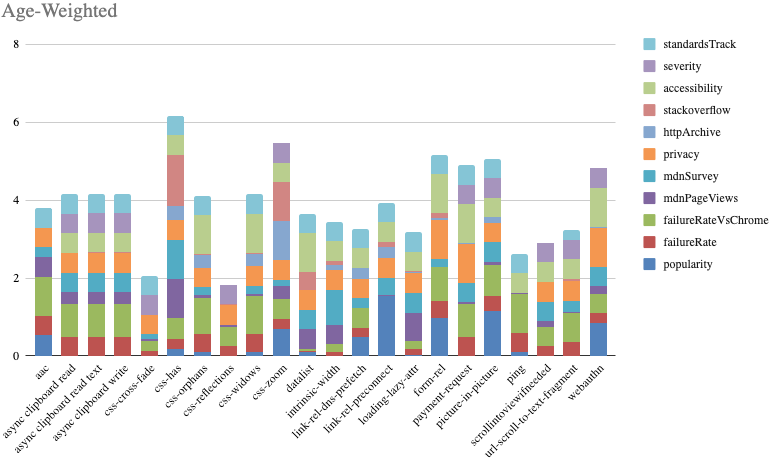

We developed a slew of metrics for measuring the popularity of a web-platform feature. They included results of a web-developer survey we conducted, traffic analysis of MDN documentation, total number of mentions on Stack Overflow, the Chrome browser’s telemetry, and even actual use on the web (as reflected in the HTTP Archive dataset).

Given everything I’ve said about zoom, you might expect that it ranked low on

each of the metrics. If that’s the case, you’ll want to sit down for this next

part:

zoom ranked near the top of most metrics, scoring second place overall.

It’d be easy to conclude simply that our metrics sucked. I wish you’d cut me a little more slack, but you don’t even know me, so whatever.

The truth is zoom’s apparent popularity is overblown by a surprising yet

ultimately-irrelevant use-case. See, zoom was also a sort of “one weird

trick” for getting IE to behave more like standards-compliant

browsers.

Here’s the short version: you would set it to the default value of 1 to make

IE chill without impacting the behavior of any other browser. That technique is

becoming increasingly useless trivia because IE 8 fixed the

problem, and IE 11 ended

the browser’s lineage. These days, you mostly only see the pattern in old

versions of the “clearfix

hack”.

If setting zoom to 1 only fixes a defunct browser, then surely we should

ignore that kind of use in our calculations, right? We couldn’t restrict all of

our metrics in this way, but it was trivial to ignore zoom: 1 in our trawl of

actual web pages.

Well, almost trivial. When we initially searched the HTTP Archive for zoom

usage, we used a somewhat-complex regular expression to avoid false positives:

\bzoom\s*:\s*([0-9]+%?|[0-9]*\.[0-9]+%?|normal|reset|inherit|initial|revert|revert-layer|unset)\s*[;\n}]

Although simplicity is a virtue, we went “full RegExp junkie” to avoid false

positives. “zoom” is a fairly common word in modern English text, and we wanted

to be sure we weren’t counting pages with content like, “Okay, zoomer,” and

“Zoom was revealed to be repurposing private user data to train machine

learning models.” To

exclude 1 from that pattern, we had to complicate it further1:

\bzoom\s*:\s*(\+?[0-9]*[02-9]|\+?[0-9]*[1-9][0-9]*1|\+?[0-9]+%|\+?[0-9]*\.[0-9]+%?|normal|reset|inherit|initial|revert|revert-layer|unset)[;\n}]

And sure enough, that reduced the number of matches by over 94%:

| zoom value | pages |

|---|---|

| any value | 20,161,142 |

| meaningful value | 1,123,519 |

Such a drastic reduction in one metric would certainly be reflected as a significant reduction in the others. We encouraged Mozilla to focus their efforts elsewhere.

Resurgence

Of course, no decision about web interoperability can be distilled into mathematical analysis. We tried to account for this by including an interactive spreadsheet in our report–one that allowed viewers to apply their own weights to each metric. Unfortunately, even our fancy spreadsheet couldn’t capture the richness of the considerations at play. I daresay no one could author a spreadsheet so fancy that it could capture that richness.

Over on the Firefox bug tracker, web developers continued to assert the

criticality of zoom’s layout-affecting

behavior (the part that

can’t be replicated with transform):

And lest anyone consider it a fringe interest, some very highly-trafficked

applications (Microsoft Excel for Web and the GMail Mobile Web App) needed the

layout effects specifically. In 2023, the CSS Working Group came up with a

clever path

forward:

write a specification for a new kind of zoom (one with fewer quirks2), and

have everyone implement that. They wrote the

spec and proposed it for

prioritization. The

Interop Project accepted it in

Interop

2025,

and today, it enjoys fairly comprehensive

support.3

And it only took 25 years!

What can we learn from this tale of frustration and woe? I’m happy to humbly offer my takeaways as a web developer who witnessed this story. I can also haughtily dispense my assessment as the incredible consultant who nurtured the evolution.

First of all: never count out the web. Consensus is not the quickest form of deliberation, but it fosters the creative and inclusive solutions that a global programming platform needs. Second: don’t build on proprietary technology. In the best case, you’re calcifying insular functionality; in the worst, you’re sowing the seeds of disappointment when license-holders change their minds or cease to exist altogether. And third: Gone In Sixty Seconds was just okay. Not great, but not terrible, either.

-

Negative lookahead would have made this a whole lot easier, but that’s not available in BigQuery. ↩

-

But not quirk-free! For example,

zoom: 0is equivalent tozoom: 1in order to preserve the functionality of some websites. The fact that some of you wrotezoom: 0and need it to do nothing only furthers my argument that software developers are the most chaotic professionals to ever be considered engineers. ↩ -

Though this summary admittedly papers over the hardships in actually bringing this to life. Mozilla, for instance, had to reckon with all the pages that use

-moz-transformalongsidezoomas a means to cover all the bases. Simply addingzoomto Firefox would have resulted in double zooming for those pages. It truly is a tangled web. ↩